Energy budget¶

The energy module computes the temperature of individual leaves based on a detailed energy balance model (see Supporting Information S3 in Albasha et al., 2019).

Energy gain of each leaf comes from:

- the absorbed shortwave;

- thermal longwave radiation from the sky;

- thermal longwave radiation from the sky;

- thermal longwave radiation from the soil;

- thermal longwave radiation from the neighbouring leaves.

Energy loss of each leaf is due to

- thermal longwave radiation emitted by the leaf

- latent heat due to transpiration (evaporative cooling)

Energy gain or loss may result from heat exchange between the each leaf and the surrounding air by thermal conduction-convection.

The resulting leaf-scale energy balance equation writes:

where \(i\) refers to leaf identifier, \(j\) refers to neighbouring leaves identifier, \(\Omega\) denotes the upper hemisphere surrounding the leaf \(i\), \(\alpha_{R_g} \ [-]\) is lumped leaf absorptance in the shortwave band, \(\Phi_{R_g} \ [W \ m_{leaf}^{-2}]\) flux density of shortwave global irradiance, \(\epsilon_{leaf} \ [-]\) emissivity-absorptivity coefficients of the leaf, \(\epsilon_{sky} \ [-]\) emissivity-absorptivity coefficients of the leaf, \(\epsilon_{soil} \ [-]\) emissivity-absorptivity coefficients of the soil, \(\lambda \ [W \ s \ {mol}^{-1}]\) is latent heat for vaporization, \(\sigma \ [W \ m^{-2} \ K^{-4}]\) the Stefan-Boltzmann constant, \(k_{sky} \ [-]\) form factor of the sky, \(k_{soil} \ [-]\) form factor of the soil, \(T \ [K]\) leaf temperature, \(T_{air}\) air temperature, \(T_{sky} \ [K]\) sky temperature, \(T_{soil} \ [K]\) soil temperature, \(K_{air} \ [W \ m^{-1} \ K^{-1}]\) the thermal conductivity of air, \(E \ [mol \ m_{leaf}^{-2} \ s^{-1}]\) transpiration flux, and \(\Delta x_i \ [m]\) thickness of the boundary layer.

Note

Only the forced convective heat transfer is currently considered in HydroShoot since forced convection dominates free convection once wind speed exceeds roughly 0.1 \(m \ s^{-1}\) (Nobel 2005). This wind speed threshold is generally exceeded during diurnal hours. However, under low wind conditions heat transfer may be underestimated.

Sky and soil form factors: the Pirouette Cacahuete issue!¶

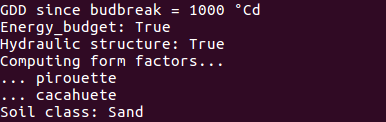

You may notice once you do your first run something like this:

This refers to the method used to calculate the lumped sky and soil form factors (respectively \(k_{sky}\) and \(k_{soil}\)).

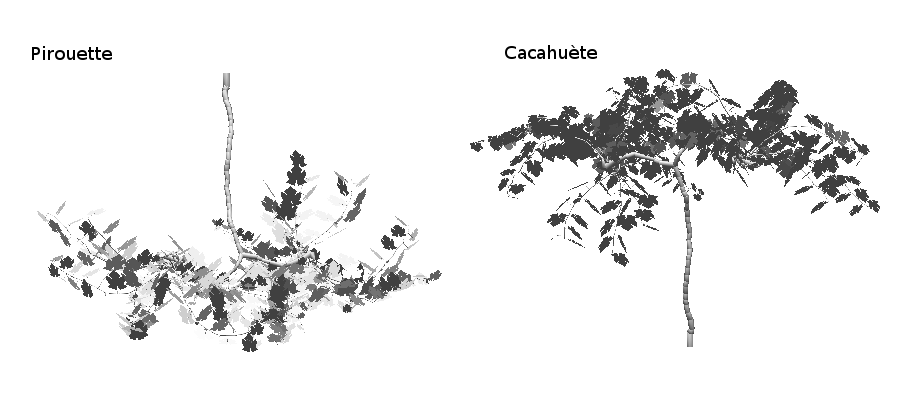

In order to reduce calculation costs, \(k_{sky}\) and \(k_{soil}\)) are obtained by flip flopping the canopy:

At first, the canopy is turned downwards. A unit irradiance is emitted from each sky sector and irradiance that is intercepted by a leaf \(i\) is assumed equivalent to the form factor between that leaf and the “soil”. In the second step, the canopy is turned upwards again and similarly, a unit irradiance is emitted from each sky sector. In this case, irradiance that is intercepted by a leaf \(i\) is assumed equivalent to the form factor between that leaf and the “sky”.

This method is clearly not 100% precise. It may need further improvements in the future.